- 1 -

Privacy Policy Manager

September 2016 - Now

Partially Shipped, Work-In-Progress

Interaction Design

Mobile Privacy

Information Architecture

BACKGROUND

With the prevalence of sensor-based smart phone apps, mobile data privacy is getting more and more complex.

This project is a collaboration between CMU, DARPA, BBN, and Invincea, with the aim to achieve an order of magnitude improvements for mobile privacy. As the designer on the team (advised by Professor Jason Hong), my role is to reimagine the UX and UI for privacy settings in a privacy-enhanced Android OS.

This project is still work-in-progress.

GETTING STARTED

With better privacy protection comes greater design challenge

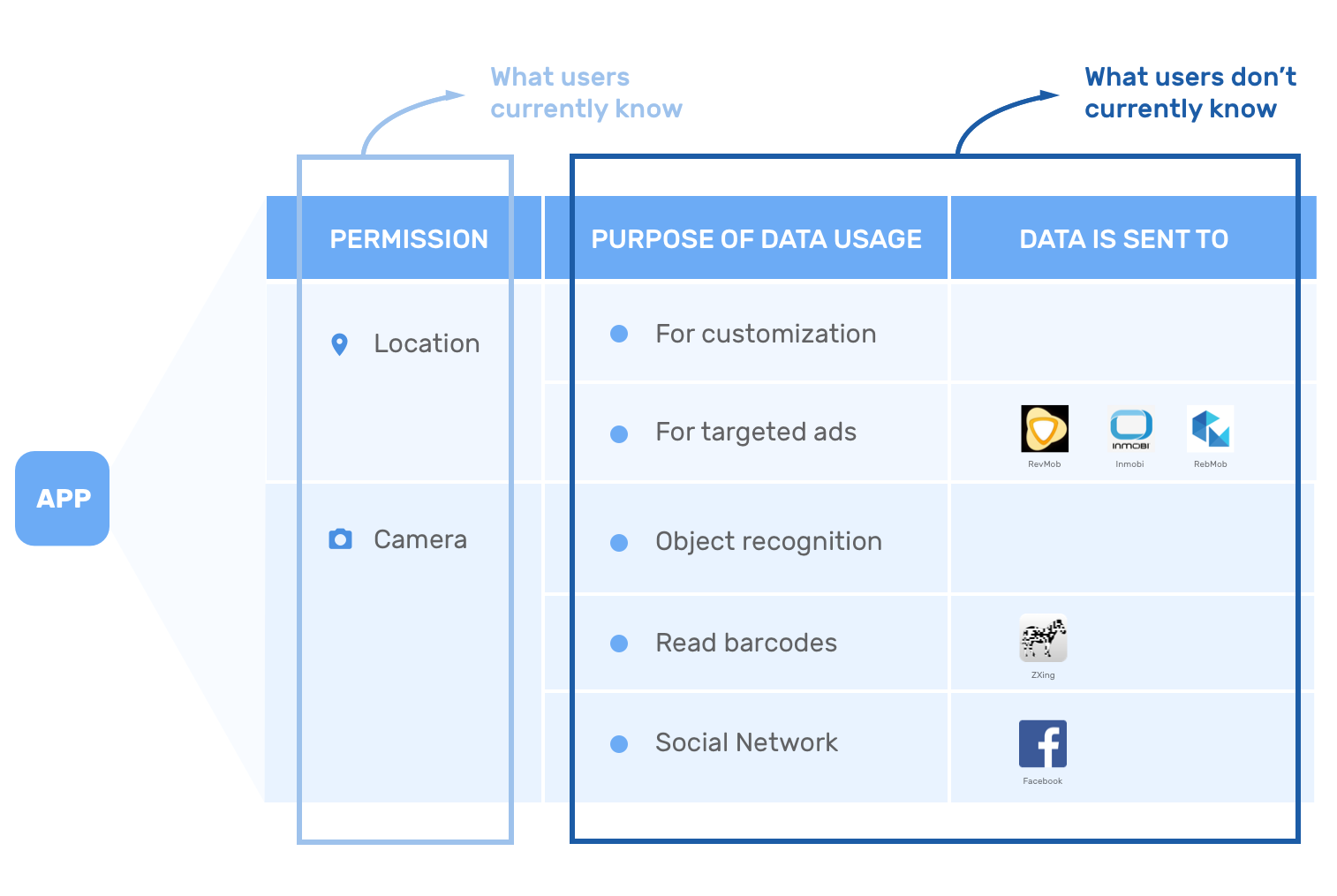

In current Android OS, apps tell you what permissions they are using (e.g. location, camera), but they don't tell you

- Why they are using these permissions (e.g. for advertising)

- Who they are sending their data to (e.g. to third-party libraries like AdMob)

In this project, we are building a future in which users can know all those information.

Our project shows user what the permissions are used for and who are the data being sent to

This is the new data model that DARPA and CMU will be proposing to Android: all Android developers need to specify the purpose of each privacy data use; on top of that, we can now parse out what third-party libraries are using what privacy data.

Engineers have done the ground work. But now, here come the design challenges:

- How can we transfer all these data onto a ~2x4 inch mobile screen?

- How can we make sure privacy settings are easy to understand and manage?

- How can we best protect users' mobile privacy under this new paradigm?

FAIL FAST, ITERATE FAST

Through an interactive design process, I was quickly moving between paper and digital prototyping, testing prototypes with users, and co-creating with and getting feedback from my advisor and engineers. From each iteration, I learned something valuable. Some helped me make small usability improvements, some helped me make major changes in my design direction.

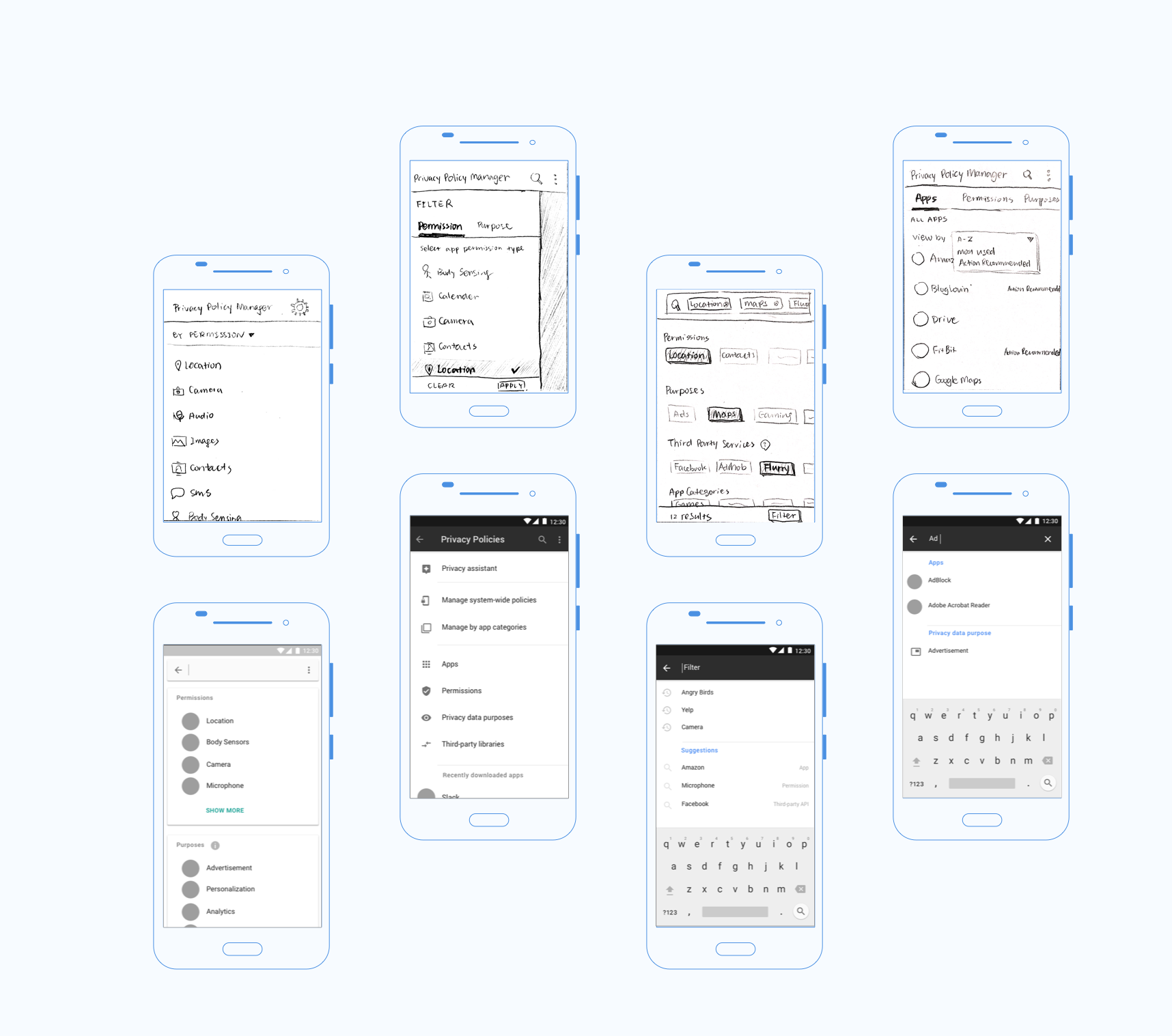

Initial iterations focused on flexible filtering

I began my early ideation based on the following scenarios:

- Which apps of mine use location data? (view by permission)

- Which apps of mine use my data for advertising? (view by purpose)

- What permission does this app request for and why?

- What are the unusual behaviors of my apps and what actions do I need to take?

My initial prototypes were focused on a flexible data filtering so that users can manage their privacy data in different views: app, permission, purpose, and third-party library. With research, I experimented with all different ways of organizing the data, from traditional filtering, faceted metadata, to search-as-filter.

Initial prototypes explored ways to efficiently filter and search for apps, permission, purposes, and third-party libraries.

LEARNING FROM USERS

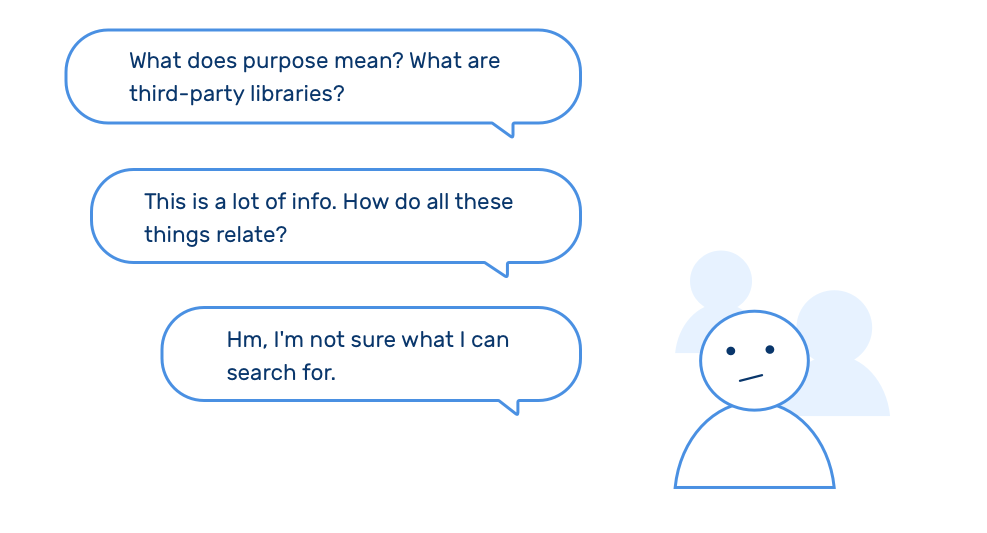

Users didn’t even know what to look, filter or search for

From testing my prototypes with users, I learned that powerful functionality is useless unless users actually understand the subject matter (privacy) and have a clear mental model of the data structure.

Users were confused about the terms and the structure in initial iterations.

While these prototypes are powerful in finding apps with specific purposes and permissions (e.g. find the apps that use my location data for ads), people were not able to effectively it. There's a lot more education work to do.

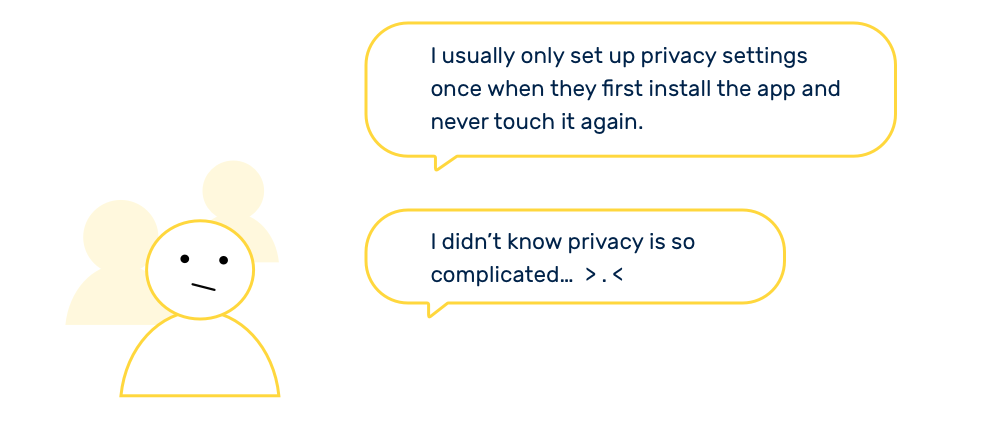

People think they care about privacy, but in reality, no so much

Another interesting finding from user interviews and tests is that people don't care about privacy as much as they think. During the tests, they often lacked the motivation to actually delve into privacy settings and manage.

Users don't actually care about privacy as much as they think.

This means:

- Install-time privacy setting UI is crucial.

It’s likely to be the only time that most users will review their privacy settings. (The install-time UI is still work-in-progress.) - We need to convince people to care more.

Users don't about their privacy as much as they think. - We need to further simplify the configuration.

- Minimize the number of clicks needed to set things up

- Less text, more icons, easier to read with progressive disclosure

DESIGN DECISIONS

We can only expect behavioral change after emotional and cognitive change. After all, the goal is to help users best protect their mobile privacy.

Onboarding tutorial helped users learn about data privacy and build up the mental model

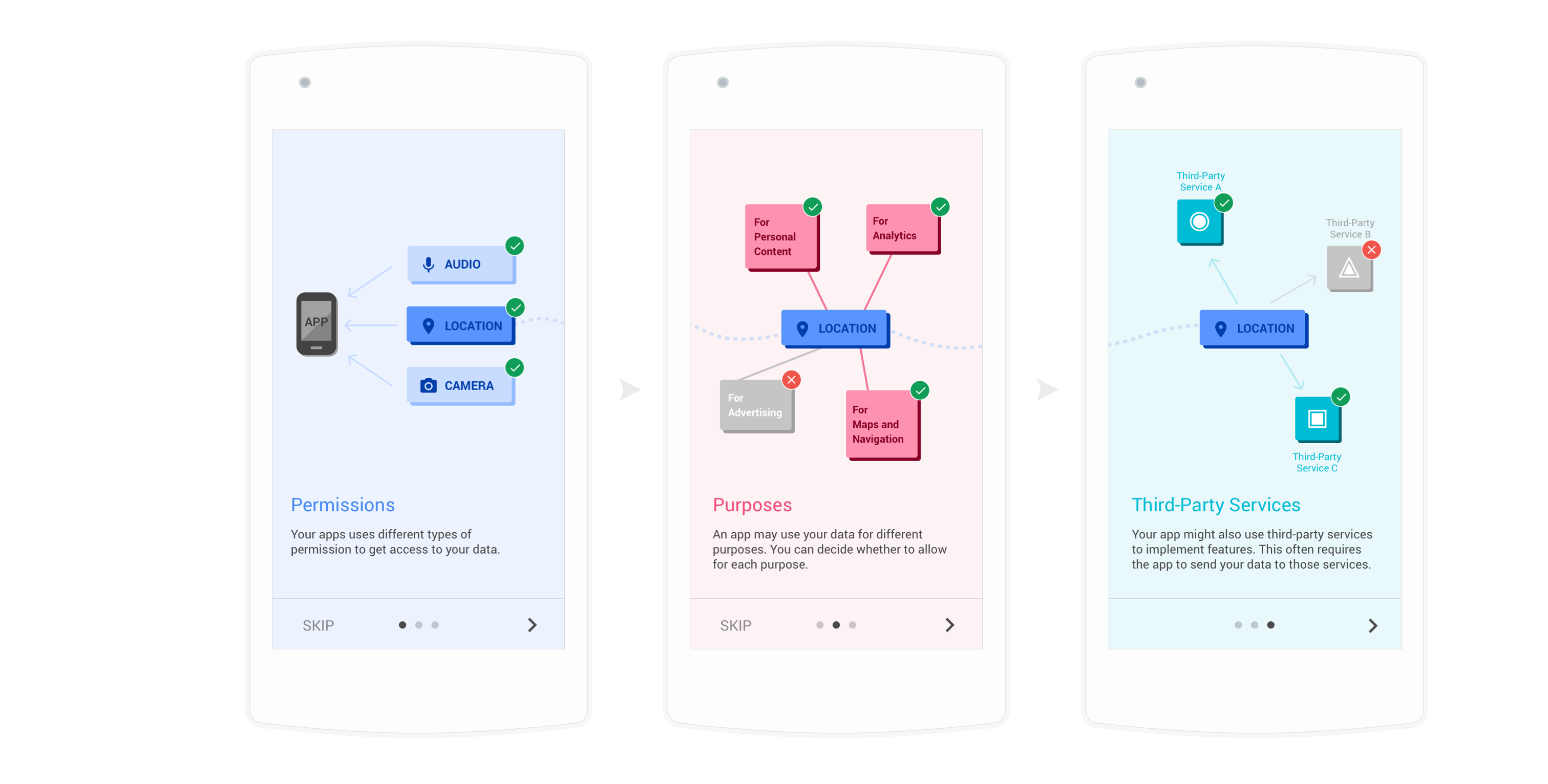

Action: I created an onboarding tutorial to educate users of their data privacy, introducing the concept of permissions, purposes, and third-party libraries.

Result: Users were able to have a much more clear mental model when they go into settings.

Onboarding tutorial explains permissions, purposes, and third-party libraries

A more exploratory design lead to less confused and more engaged users

Action: Instead of just giving users category titles of privacy data, I decided to show more detailed examples of apps and types of privacy information upfront, to help users explore possibilities.

Result: Users expressed fewer confusions, became more engaged, and showed more interest in managing their data privacy.

Giving more detailed examples of privacy categories incentivises users to explore more.

Applying crowdsourced recommended settings made only a button away

Action: While users can still micro-manage every single privacy setting, I also made the "Apply Recommended Settings" a prominent call-to-action. The user can preview the recommended settings before deciding whether to apply.

Result: Users, "Whew, this is so much easier! I trust Android's judgment."

Giving more detailed examples of privacy categories incentivises users to explore more.

Privacy data broken down into bite-sized bits

Action: Showing all the privacy data at one time turned out to be too overwhelming for normal users. Showing the data in bits and pieces helps reduce the mental strain the privacy settings impose on users.

Result: Users are less overwhelmed. The privacy settings are now more digestible.

Progressive disclosure (hiding secondary information and layering) creates and hierarchy and makes the information volume not as overwhelming.

I'm continuing to work on this project in the spring semester. There are a lot more things to be explored, such as designing effective install-time UI, making the prototype more high-fidelity, and evaluating the effective of the current iteration with more users, etc.

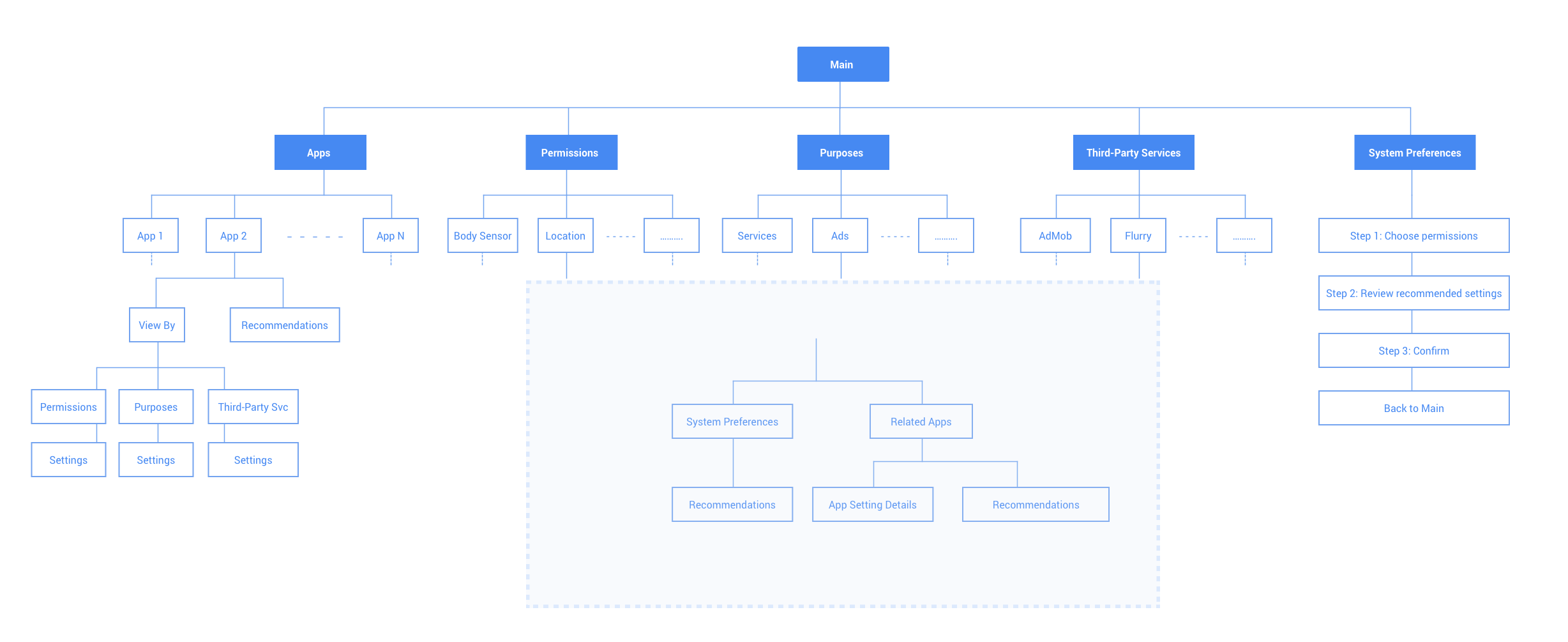

Sitemap of the latest iteration

REFLECTIONS

Always validate design assumptions with users

Designers and engineers often know “too much” to make good assumptions about the product or the user. Had I not test my early iterations with real users, I would not have changed my focus from how can I allow users to flexibly manage their data privacy, to how can I encourage them the care about data privacy and explore the possibilities.

Be proactive, be collaborative

As this is an independent study project, I was managing my own workflow and deadlines. I was proactive through the entire process, communicating with my team, collecting feedback, and getting the resources when needed. The help, insights, and co-creation I received from my advisor, the engineers I worked with, peer designers, and users were invaluable. All these brought me closer to achieving the initial project goals.

If you are interested in this project and want to take a closer look at the prototype, feel free to reach out! Also, check out other cool projects at CMU CHIMPS Lab that involve ubiquitous computing and usable privacy and security.